Hundreds charged with treason in #Tanzania as authorities hunt key opposition figures after election.

In addition to dozens criminally charged a day earlier in Dar es Salaam, dozens more face similar treason charges elsewhere in the East African nation, according to numerous charge sheets that became publicly available Saturday.

Wanted suspects include Josephat Gwajima, an influential preacher who had his church deregistered earlier this year after he criticized the government over rights abuses.

Police also issued arrest warrants for some of the top opposition officials who hadn’t yet been jailed. They include Brenda Rupia, communications director for the Chadema opposition group, as well as John Mnyika, its secretary-general.

Chadema is Tanzania’s leading opposition party. Its leader, Tundu Lissu, has been jailed for several months and also faces treason charges after he urged electoral reforms before voting on Oct. 29.

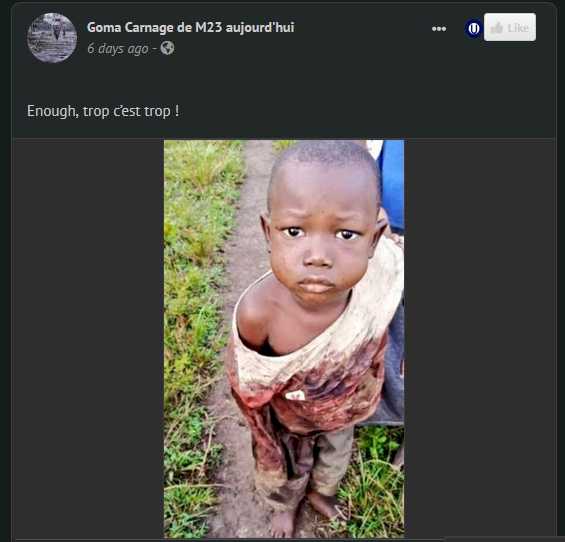

Authorities face questions over the death toll after security forces tried to quell riots and opposition protests before and after the vote. Chadema has claimed that more than 1,000 people were killed and that security forces were trying to hide the scale of the deaths by secretly disposing of the bodies. The Catholic Church in Tanzania has said that hundreds were likely killed.

But some believe that the death toll could actually be much higher. The Kenya Human Rights Commission, a watchdog group in the neighboring country, asserted in a statement on Friday that 3,000 people have been killed by Tanzania’s security forces, with thousands still missing.

“Amidst the ongoing attempted cover-up, facilitated by the continued internet blackout and bandwidth restrictions, this number could be thousands below the actual death toll,” the statement said.

Pictorial evidence in the rights group’s possession shows many victims “bore head and chest gunshot wounds, leaving no doubt these were targeted killings, not crowd-control actions,” it said.

President Samia Suluhu Hassan, who automatically took office as vice president in 2021 after the death of her predecessor, took more than 97% of the vote, according to an official tally. She faced 16 candidates from smaller parties after Lissu and Luhaga Mpina, of the ACT-Wazalendo party, were barred from running.

Rights groups described a climate of repression before voting. There were enforced disappearances, arbitrary arrests and extrajudicial killings, according to Amnesty International and others. Tanzania’s government denies the allegations.

The African Union said this week that its observers had concluded that the election “did not comply with AU principles, normative frameworks, and other international obligations and standards for democratic elections.”

AU observers reported ballot stuffing at several polling stations, and cases where voters were issued multiple ballots. The environment surrounding the election was “not conducive to peaceful conduct and acceptance of electoral outcomes,” the statement said.

Africa news on Umojja.com