An ‘existential gamble’: Why some experts are worried as SpaceX gears up for next Starship test.

The most powerful rocket system ever constructed is headed for its next test — using a version of the vehicle that has been at the center of a series of explosive missteps and failures.

SpaceX said it is aiming to launch its Starship megarocket on an hour-long test flight as soon as 7:30 p.m. ET Sunday, though the liftoff time is subject to change. A webcast of the event is expected to begin about 30 minutes earlier, according to the company.

The uncrewed Starship prototype will follow a similar flight plan to the last three missions and aim to complete test objectives left untried during those tests, all of which ended prematurely. SpaceX debuted the current generation of Starship vehicles in January, following a clean run of test missions with a slightly scaled-down version of the rocket in 2024.

But since that debut, the vehicle has twice exploded over populated islands east of Florida, creating debris that hit roadways in Turks and Caicos and washed up onto the shores of Bahamian islands. The spacecraft also spun out of control as it headed toward its landing site in the Indian Ocean on its last test flight in May.

Then, in June, a Starship spacecraft that had been strapped to an engine testing stand at the company’s launch and development facilities in South Texas abruptly exploded — spewing shrapnel and causing damage to SpaceX infrastructure.

These setbacks roused long-standing SpaceX critics and attracted new ones, including the Mexican government, which has threatened legal action against the company over reported debris on and around its shores. The UK government also said in a statement Thursday that it’s been “working closely with U.S. Government partners to protect the safety” of its overseas territories, including Turks and Caicos.

The string of mishaps this year has also raised concerns among spaceflight experts and stakeholders who have emphasized that the United States has a lot riding on Starship’s eventual success, including its plans to return humans to the moon as soon as 2027.

And that success is not guaranteed.

“It’s very, very difficult to predict how this is going to end up,” said Garrett Reisman, a former NASA astronaut and SpaceX consultant who is a professor of astronautical engineering at the University of Southern California.

“I think it could end up never working, or it could end up revolutionizing our entire future of activities in space — and geopolitics,” he added, referring to the U.S. goal of displaying technical superiority to China in a new space race.

Why SpaceX is allowed to fly again

SpaceX said it implemented changes to the Starship system slated to fly this weekend in response to the last in-flight failure in May.

Those alterations include adjustments to a component called a fuel diffuser, which the company believes malfunctioned during the last flight, causing higher-than-expected pressure to build up in Starship’s nose cone. It is likely what caused the vehicle to spiral out of control, according to a technical overview SpaceX published last week.

Despite the series of recent problems, the Federal Aviation Administration — which licenses commercial rocket launches — said last week it had closed its investigation into SpaceX’s latest mishap and approved the company’s plans to fly Sunday’s mission.

Under current laws and regulations, the FAA is tasked solely with ensuring that commercial rocket companies do not pose a risk to public property or bystanders’ safety.

“There are no reports of public injury or damage to public property. The FAA oversaw and accepted the findings of the SpaceX-led investigation,” the agency said in an August 15 statement. “SpaceX identified corrective actions to prevent a reoccurrence of the event.”

A long road ahead

In its update, SpaceX also made clear that the version of Starship that has experienced so many issues will soon be retired.

“Two flights remain with the current generation, each with test objectives designed to expand the envelope on vehicle capabilities,” according to a company blog post.

SpaceX CEO Elon Musk has already been teasing plans for larger, more ambitious iterations of the vehicle that would stretch even taller and carry more propellant.

Now it appears clear that SpaceX will pursue that scaled-up version of Starship — which is already more than twice as powerful as the NASA rockets that powered the Apollo moon landings — whether or not the current line of Starship prototypes ever pulls off a successful test flight.

“It’s very possible that a bigger upgrade might solve the current problem,” Reisman said. “It also could introduce new problems — you never know.”

Notably, the U.S. government has taken several steps that could aide SpaceX in its efforts to expedite Starship testing.

In May, the FAA approved the company’s plans to launch Starship as many as 25 times per year from Texas, up from the five it had been previously authorized to conduct.

And earlier this month, U.S. President Donald Trump — despite a public and vitriolic falling out with Musk in June — issued an executive order that appears designed to scale back roadblocks and regulatory oversight for private-sector rocket operations, including environmental reviews.

Meanwhile, the stakes appear to be growing with each Starship test flight, as SpaceX is racing against the clock.

Not only does Musk want to send one of the vehicles on an uncrewed flight to Mars when the next opportunity arises in 2026, but NASA also plans to send its astronauts to the lunar surface aboard one of the vehicles as soon as mid-2027 as part of a $2.9 billion contract.

“We made this bet” on Starship, said Janet Petro, who served as acting NASA administrator until July. “They have had a rough year, but SpaceX is a pretty intense and motivated company.”

Petro added she had “full confidence” that SpaceX will refine Starship’s design and get the vehicle working.

Reisman, the former SpaceX adviser, said he is also hopeful but less certain.

“SpaceX has made an existential gamble on Starship,” Reisman said, adding that he is concerned about the rate of progress SpaceX has been making with Starship. “They’re pouring a tremendous amount of money and resources into its development … but at some point, the laws of financial physics still apply.”

What SpaceX hopes to achieve with Flight 10

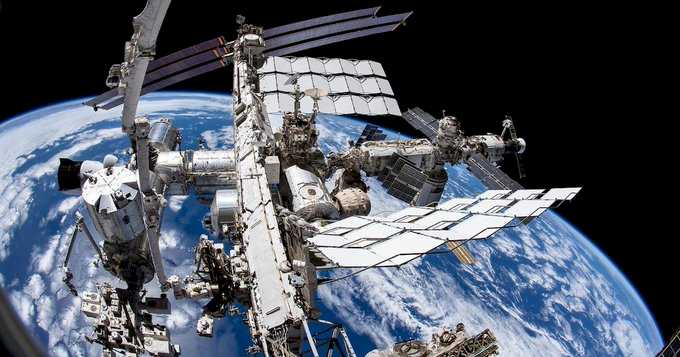

If all goes according to plan with Starship’s next flight, referred to as Flight 10, the 400-foot-tall Starship launch system will take off from SpaceX’s facilities in South Texas and soar out over the waters off the coast.

The bottom portion of the rocket system that gives the initial burst of power at liftoff, called Super Heavy, will attempt to make a controlled splashdown off the Texas coast, according to SpaceX.

For this mission, the company will not attempt to repeat its dramatic Super Heavy “chopsticks” landing in which the rocket booster steers itself back into the arms of the tower from which it launched. SpaceX said it will instead put the booster through a series of tests designed to push the vehicle to its limits “to gather real-world performance data” that could mimic a future mission that does not go as planned.

Meanwhile, the upper Starship spacecraft, which is designed to one day carry cargo or convoys of astronauts but will haul only dummy satellites for this mission, will continue flying through space.

During the flight, Starship will attempt to deploy the eight satellite “simulators” as well as relight one of the spacecraft’s rocket engines in space. SpaceX has failed to hit both of those milestones in its last three test missions.

Even if this V2 Starship prototype meets a similarly ill fate, SpaceX is likely once again to frame the test flight as a success.

The company employs an engineering philosophy called “rapid iterative development,” which emphasizes a pursuit of launching relatively cheap prototypes on frequent test missions over extensive ground testing or other less risky simulations.

Because of its unique development approach, SpaceX has been known to embrace fiery mishaps. The company has said that even failed test flights help engineers improve Starship’s design — quicker than if SpaceX employed alternative engineering approaches.

“Every lesson learned, through both flight and ground testing, continues to feed directly into designs for the next generation of Starship and Super Heavy,” SpaceX’s August 15 statement reads. “Two flights remain with the current generation, each with test objectives designed to expand the envelope on vehicle capabilities as we iterate towards fully and rapidly reusable, reliable rockets.”

SpaceX’s development approach, while often seen as risky and brazen, has served the company well in the past.

Rarely has one of the company’s rockets malfunctioned once it leaves the development stage and becomes operational. The company’s human spaceflight track record, using Falcon 9 rockets, has been spotless.

And if Starship does eventually work, Reisman said, it won’t only be SpaceX — or even NASA — that benefits.

“The entire space industry is hoping and betting on Starship working, because if it achieves its promise, it’ll also be a revolution in affordability,” Reisman said. “I think there’s causes for optimism and pessimism — and I think it’s very, very difficult to predict how this is going to end up.”

By Jackie Wattles, CNN

Space news on Umojja.com